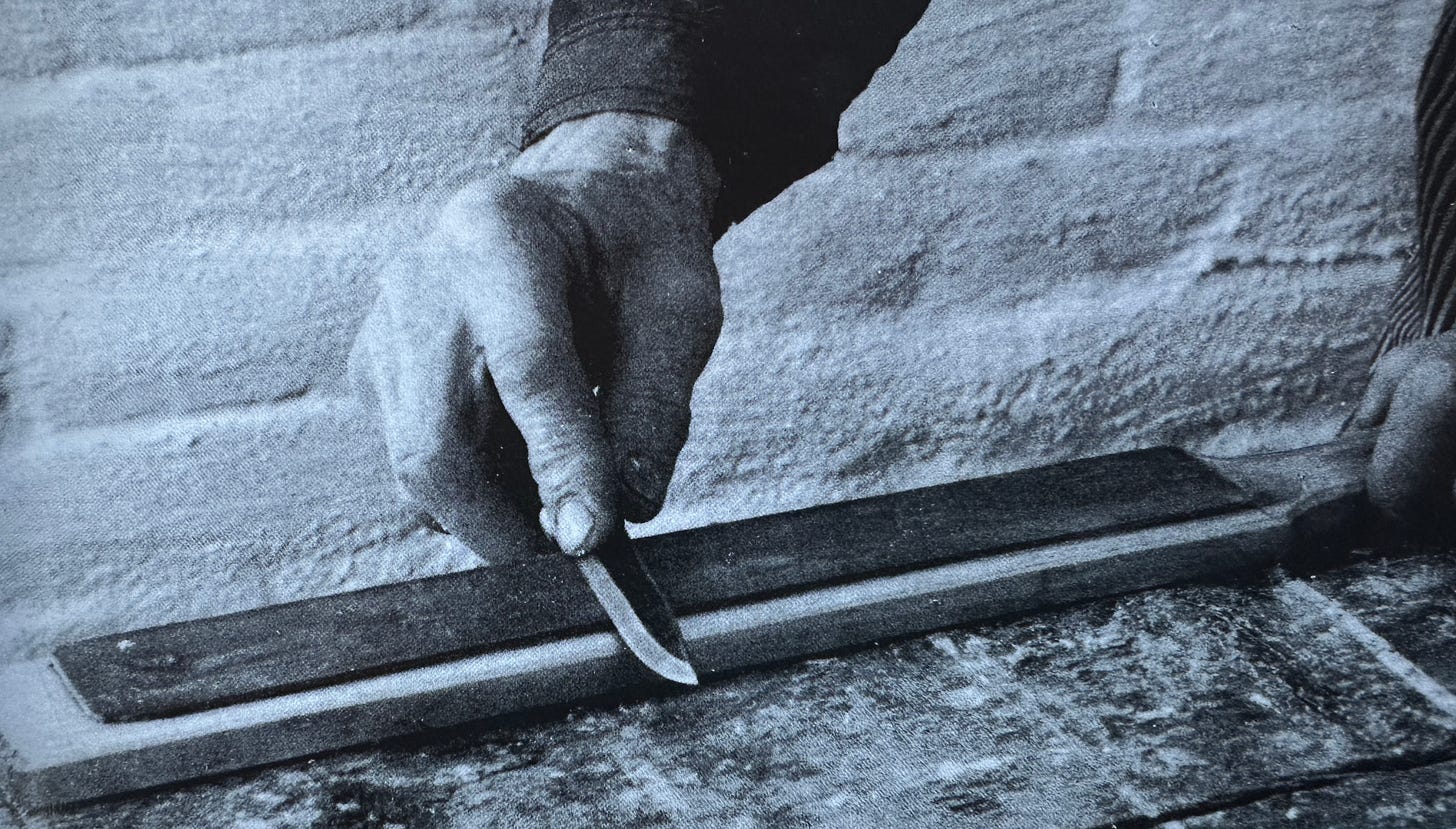

Man On Sharpening the Blade

The Problem with Turning Vice into Virtue

Perhaps the most iconic of American architects is Frank Lloyd Wright, and this is due primarily to his landmark project, Fallingwater. As legend has it, Wright procrastinated for months until his client, the department store magnate E.J. Kaufman, was on the way to visit Wright to check on his progress. With a few hours to spare, Wright quickly drafted the plans for Fallingwater, and this first draft was the final draft; Kaufman approved the plan.1

This tale is spun as a showcase of procrastination’s benefits; subconscious incubation of ideas yielded a miraculous jolt of genius in the form of Wright’s “Lightning Sketch.” Is the delay of real work like an idea composting underground, or is it justifying inefficiency?

My greatest procrastination to date occurred before writing a gear review article. Starting it alluded me. I decided that before I could begin, I needed a new desk. Buying the desk I really wanted would have cost a couple of thousand dollars, which I wasn’t willing to pay. The cheaper ones seemed just that: cheap. So I would build my own desk.

But before that, I needed to decide on the species of wood I would use. I reasoned that making my own lumber for the desk project made sense. Find the tree, cut it down, season the lumber. And voilà, once the three coats of polyurethane had dried on my new desk, I could start writing the article I had agreed to write!

I was sharpening the spear forever, avoiding the task.

Procrastination in the self-help space is traditionally viewed as an affliction to overcome. Books like The Procrastination Equation and Solving the Procrastination Puzzle promise solutions to dealing with it. In general, psychologists do not couch procrastination as serving a hidden purpose, but rather as a problem. “Procrastination is the act of intentionally delaying task progress or completion with the understanding that doing so may come at a cost” (Shin & Grant). Professionals cite self-control, self-deception, and perfectionism as typical, interrelated causes: “Procrastinators are often perfectionists, for whom it may be psychologically more acceptable never to tackle a job than to face the possibility of not doing it well.”

But what if the process of procrastinating hides something beneficial? What if, like Wright, we could delay our work until the last minute, yet still complete the job? Santella’s history of procrastination reveals variations that highlight some of the virtues of procrastination, making those who do it feel good about themselves. In a meta-analysis, Kooren et al. distinguish between passive (indecision to act) and active (deliberate decision to work under pressure) procrastination, with the latter showing moderate positive outcomes. If procrastinators like Newton, Darwin, and Wright procrastinated, why can’t I?

Maybe their genius lay in allowing their ideas to incubate? It’s an attractive proposition.

We should be skeptical of this trend of turning negatives into positives in the self-help space, however. Taking a behavior, such as procrastination, and spinning it to be positive is problematic because it leads to “there is no right answer” thinking. On this path, procrastination is a benefit and not a habit that needs reform. In this world, we waste the day, sharpen the spear forever, and only daydream about one day sinking it into the broadside of our prey.

Pen to paper, blade through flesh.

For those who can afford it (in both time and money), procrastination becomes a luxury and a justification for inaction, the adult equivalent of placing a chemistry textbook under our pillow at night in hopes that we absorb the page’s content before tomorrow’s exam.

Pre-castination, on the other hand, is defined “as the tendency to complete, or at least begin, tasks as soon as possible, even at the expense of extra physical effort.” If procrastination is delaying the chase, then precrastination is its mirror mistake: rushing to the task in an automaton-like fashion to feel busy.

In cases where procrastination yields measurable benefits in terms of creativity, the question arises whether the activity in question is, in fact, procrastination or something else entirely, such as thinking or research, both of which are necessary activities for complex tasks.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s hurried design of Fallingwater resulted in an iconic building, but also introduced unsustainable design elements that required constant repair. A consequence of procrastination? Had he not rushed at the last minute but instead considered the longevity of the structure, what would Fallingwater look like today? If his delay had been an incubation of ideas, would it have culminated in a sound design?

I still haven’t built that desk, but I did finish the article.

Don’t Delay

To be fair, building a desk sounds way cooler and more fulfilling than writing a gear review article… that being said, I’m sure your article was fantastic just like this one

How I appreciate the caveat, of sorts, leaving space for the thinking and research. I find myself wondering, when did I last procrastinate and then think when I did it was for the soft adrenaline rush of needing to hurry, to give value to my want to have control for just a few moments.