Death of the Hunter-Gatherer

Meritocracy and Spirit

When humans hunted for food out of necessity, failing meant starving.

I’ve said a variation of this statement multiple times in the Next Adventure newsletter.1 A simpler phrase is:

When hunters fail, they starve.

When I make this statement and allude to the present day, I connect our past to the now. We are all hunters, whether we like it or not. Yet some people disagree, and I want to focus on one element of this disagreement.

Perhaps it is on religious or scientific grounds.

Gathering roots and berries was important, but meat has always been the prize.

The hunt excited and challenged us. It united us in a collective celebration of our quarry, with meat routinely divided amongst group members. Various egalitarian arrangements existed in the distribution of an ungulate. From an evolutionary standpoint, we’re made to hunt.

Physiologically, our teeth developed to bite and tear animal flesh; over time, our molars, used to grind food, shrank.2

Anthropologically, what we know about modern hunters alive today living in similar circumstances as the Pleistocene is that meat remains an important staple.3

Let’s return to the offense people feel when I make the allusion between past and present. In the spirit of understanding other points of view, there are two reasons:

The Simple Reason: People don’t like the idea of killing animals.

The Complicated Reason: There’s a meritocracy implied in the statement.

Let’s explore number two.

In the ethos of “everyone gets a trophy,” my statement about failing at hunting could easily upset the sensitive among us. What lurks behind this feeling is fear. Specifically, fear of failure. We don’t want to fail or lose a contest, and we all want to win.

Let’s look at a current and well-established example: grade inflation. In math, for instance, high school students' GPAs increased by 0.30 between 2011 and 2023.4

What, then, can colleges use as a measuring stick of admission? The SATs or ACTs. Yet these are criticized for bias.5

If everyone gets an “A” and the SAT is too biased to use, how does a college determine who to admit?

To make progress, we need measurement. To have a measurement, we need structure.

What happens if we can’t gauge progress? If there is no “right” or “wrong” answer?

The inflation belies a failure-avoidant worldview where we forego the opportunity to learn. If every answer is correct or true, “depending on how you look at it,” where does that lead us in the battle between right and wrong?6

If I get a trophy regardless of whether I win or lose, what happens to my motivation to improve? Where’s my incentive to keep winning if everyone is a winner?

Returning to my original statement:

“When hunters fail, they starve.”

While the meritocracy-averse among us may balk or reject this statement outright, doing so means we miss out on a nuanced viewpoint.

What if you were maimed and injured and unable to hunt? Born with a deformity that prevented you from running?

You contributed in some way to your group, and when the meat arrived, you received some. Perhaps your role was to scrape the hides used to make the bags that carried the meat home from a hunt or the ground nuts from a distant gathering spot.

In this way, it was similar to now: there was a specialization occurring amongst the group. Not everyone could hunt (or wanted to). Calorically speaking, while meat was a bounty, there was likely enough plant matter to gather for survival.

But why, then, would we evolve such a strong physical and emotional connection to the chase of animals?

In addition to the caloric windfall, hunting provided a spark of excitement, of awe, a nourishment of spirit. Exciting in the moment? Yes. But the story of a hunt could be told and re-told, to invoke wonder and new vantage points, a type of ancient Netflix to be replayed by the flickering light of a fire.

Each time the story is told, a new lesson is learned, a perspective gained, not unlike binge-watching your favorite series after a two-year hiatus and realizing the subleties of a previously ignored character or storyline. Any contemporary fisher or hunter today is well aware of the ever-evolving stories told at camp, the pickup truck, and ammo counter: recitations never told the same way twice. The size of the rack grows, the weight of the fish inflated, and the distance of the drag multiplied. Tall tales motivate and galvanize an element of our imagination that gets us out of bed in the morning.

In this way, hunting is art.

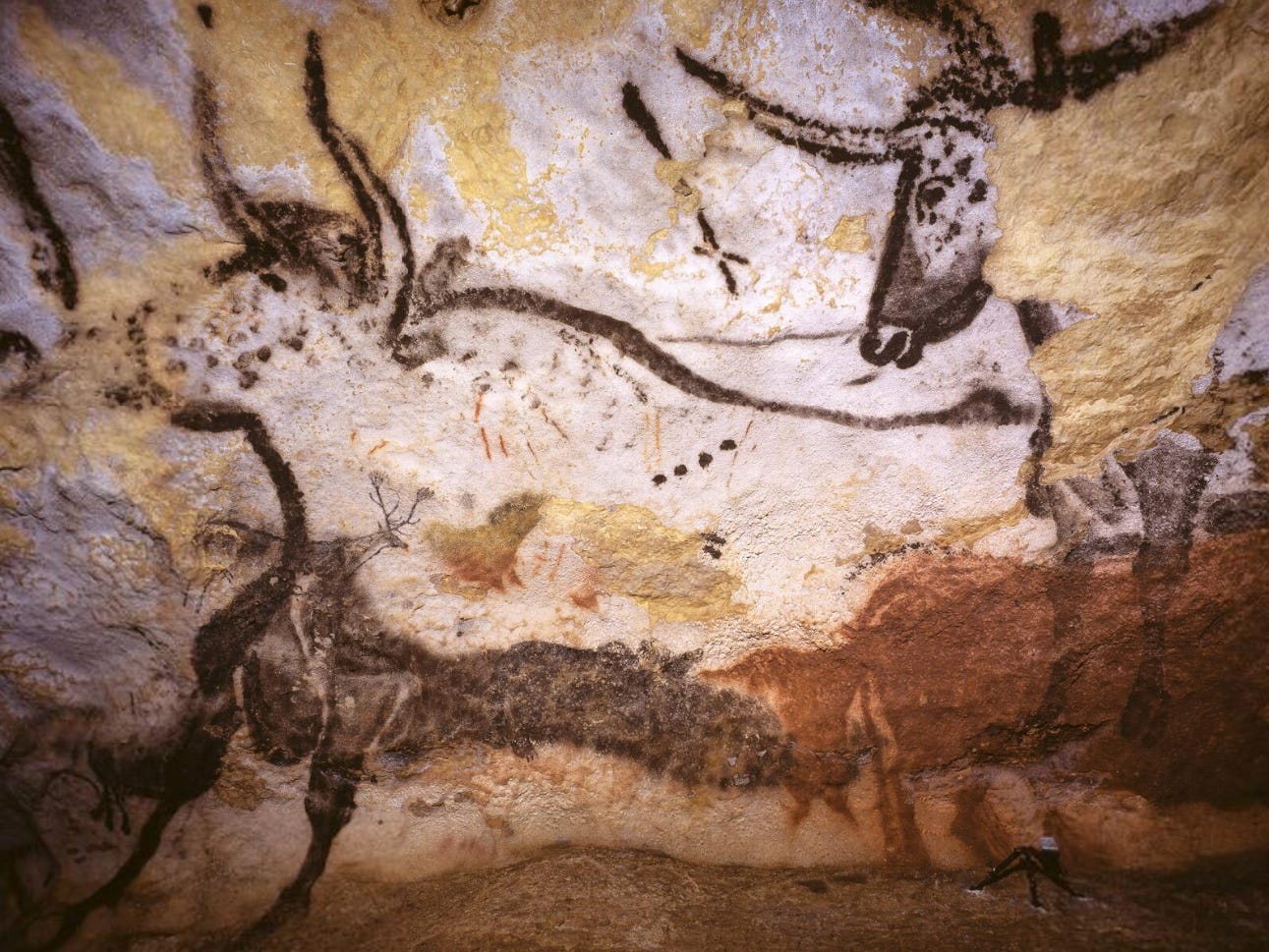

“When Paleolithic people painted on the walls of their caves, they didn’t paint grubs or baby birds, and they didn’t paint nuts, roots, or berries. No, they painted large mammals, mostly ungulates, many with projectiles sticking out of them…They were artists who knew about hunting. They were hunters who knew about art.”

- Elizabeth Marshall Thomas7

Thus, hunting isn’t a necessity for the calories; it is a necessity for inspiration, art, and, I contend, the spirit.

Once again, let’s return to the current moment.

We’ve removed some of the direct actions and consequences of our ancestors, but we still operate (somewhat) similarly in terms of specialization. But that’s where the resemblance ends. Very few are involved in meaningful acquisition of food, where daily actions have a direct impact on our own as well as the group’s survival (only a small percentage of us farm, but the few who do generate a tremendous amount of food).

Thus, the direct feedback of a close-knit tribe is missing. This is a constant evaluation that encourages us to change and learn, a cause-and-effect loop hardwired into our brains; to see, respond, act, and change.

Drawing from the grade inflation example from above, we’ve begun to aggressively short-circuit this feedback loop. Where’s the positive feedback if everyone wins? Where’s the negative feedback if everyone wins?

Let’s look from the adult perspective of an office job. What if my job feels pointless? What if there’s no clear meaning to it? Excitement? No purpose? What if “progress” becomes relative and unmeasurable? Moving and unattainable benchmarks ensure a perpetual state of hope and hopelessness. This is a feeling foreign to a hunter-gatherer used to the direct feedback of the chase and contribution to our group.

“When hunters fail, they starve.”

Superficially, this is a statement about meritocracy, but more meaningfully, it’s a statement about existence. Let’s say you fail at your hunt, or are viscerally disgusted by the idea of dressing an animal? That’s really not a problem since a role for you still exists, but only if you’re allowed to figure out what that role is.

Without any hunting, we starve–not because we’re hungry—but because we're uninspired, robbed of a spiritual enrichment that’s impossible to replicate.

What stories get repeated to inspire our children and make them wonder what’s on top of a distant ridge? Where’s the day-to-day feedback indicating we’re failing or succeeding, telling us where to improve? When stating “you're wrong” in a work meeting becomes a microaggression legislated by bloated, unnavigable HR departments, what does that do to the hunter-gatherer brain?

This is a path that leads to the death of the hunter-gatherer. Feedback becomes couched in relativity, art is AI-generated, and our children rely on Instagram reels for inspiration.

*Thank you for reading Next Adventure. Your support makes it possible to consistently publish essays. I particularly enjoy ones like this where I raise questions about the present and connect us to our past. “Liking” (❤️) helps spread the word.

“Meat in the human diet: An anthropological perspective,” Mann, 2007.

“Man the Hunter: The First Intensive Survey of a Single, Crucial Stage of Human Development― Man’s Once Universal Hunting Way of Life,” Lee & Devore, 1968.

“High School Grade Inflation on Rise, Especially in Math,” ACT

“Lawsuit Claims SAT And ACT Are Biased—Here’s What Research Says,” Elsesser, 2019.

“The Old Way,” Thomas, 2006.

Provocative. Thanks for that. When I read "The Old Way" I began to think of hunting as a social development and community structure. I've read good arguments that hunting and eventually hunting in groups drove our social connections beyond our immediate kin to larger groups: clans. Our languages became shaped by the need to communicate about sharing the harvest and various rites and ceremonies came from that. Today we run from such events by giving honors without merit and devaluing the successful harvest of the most gifted hunters.

The concept of "if we fail, we starve" is such a powerful motivation that really gets demonized in this day and age. When we have safety nets for everything in life we sort of introduce iatrogenics into a complex system- basically we cause unintended harm. Great piece!