Purpose is a Weapon

Myth, Certainty, and How We Decide

In 1984, a fisherman paddling on a small pond in Vermont observed what appeared to be a floating log. It was the camouflaged hull of a dugout canoe, dating back to 1500. The canoe, used to travel the length of the pond for hunting and trapping, was too heavy for long-distance travel. After academics studied the canoe, they resubmerged it— an effort to preserve it for future study. The canoe hadn’t changed, but the story told about this pond did. People assigned a new definition to this place, and a new factual certainty took hold.

We habitually think about the histories of the places we live in and visit. Sometimes it’s research, sometimes imagination. While hiking the Green Mountains this fall, I considered: Who else lived and hunted here? As I looked west over Lake Champlain and onto the Adirondack Mountains, the daydream consumed my imagination. Quiet and snowy, with no visible houses, lights, or engine noises, it was easy to conjure up images of people traveling the length of the lake. A few weeks later in the Adirondacks, I wondered how many dugout canoes lie sealed under the dark water.

It’s hard not to feel a connection to the land and to ancient people when traveling any stretch of woods. Imagining ties between an ancient people and the present is, at best, an exercise in solidarity and connection, which is an enjoyable feeling. At its worst, it’s naive in the sense that it glosses over the struggle and bloodshed that define human territoriality. As stories become certain, they make decisions for us.

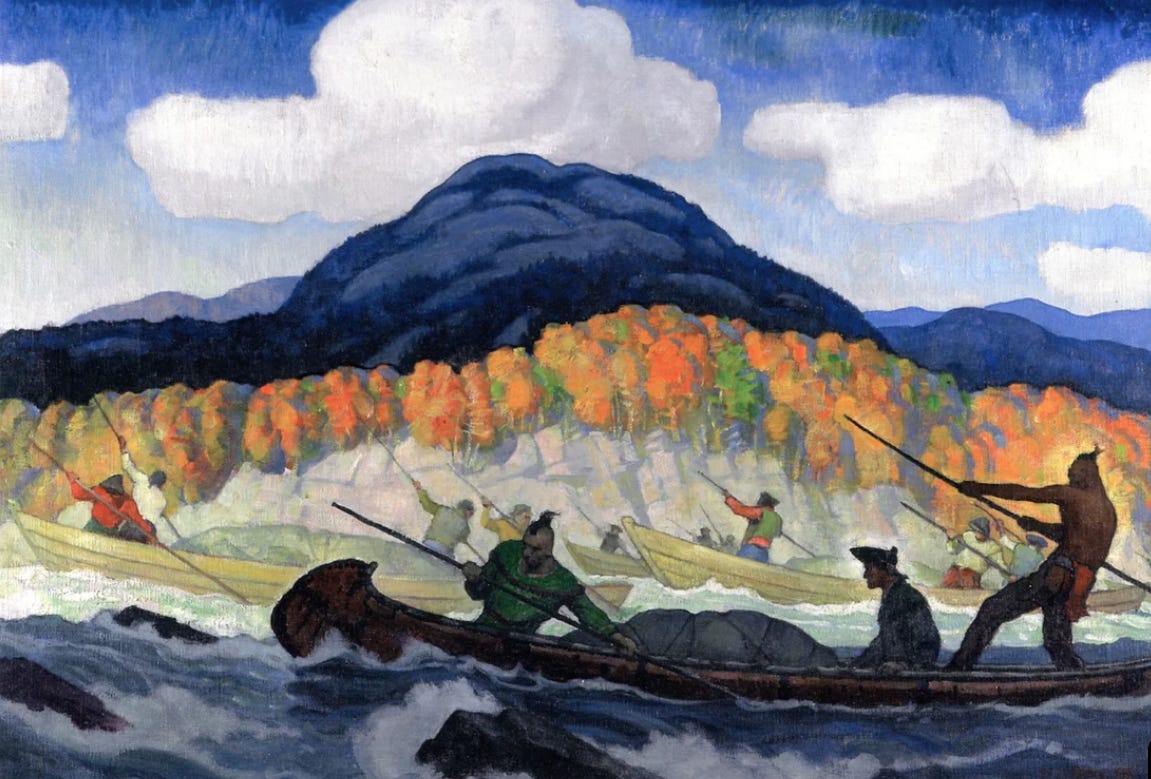

Champlain

As imagination, belief, and knowledge converge, there’s a human tendency to assert a combination of these as fact, as in the case of most mythmaking. Belief is private, whereas knowing with conviction feels like a fact. The courage of explorers such as Samuel de Champlain was grounded not only in cartographic mastery but also in a sense of purpose, a precursor to Manifest Destiny. Notice how Champlain observes and then concludes with duty, not more inquiry:

“as I had observed in my previous journeys, there were in some places people permanently settled, who were fond of the cultivation of the soil, but who had neither faith nor law, and lived without God and religion, like brute beasts. In view of this, I felt convinced that I should be committing a grave offence if I did not take it upon myself to devise some means of bringing them to the knowledge of God.” (Champlain)

Ego? Money? God? Certainty gave him permission.

Champlain overcame doubt, fear, and criticism because a force possessed him, a force that brought him to a place of certainty in his part of history.

Knowing is both powerful in steadying the unknown, but it also tends to make the unknown submit as a means of control.

Hiawatha

Four hundred years before Champlain observed the great lake that separates Vermont and New York, the mourning wars among tribes of precolonial America involved long cycles of violence. That cycle ended with Hiawatha. A depressed Onondaga warrior who, after losing his family in war, joined the Great Peacemaker to end seemingly endless bloodshed among the Haudenosaunee nations. A transformed Hiawatha, no longer in mourning, became a war-shaped leader of peace, who allied the five nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy has been dated to around the year 1200 (though this date is contested), with each nation joining to achieve a combination of economic, cultural, and political stability. The Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Oneida tribes formed a Confederacy that became a dominant force in the region, with each group controlling its own territory.

“The Mohawks were the guardians of the eastern door in the lower Mohawk Valley area. The Oneidas occupied the upper Mohawk Valley and the area of modern day Oneida, NY. The Onondagas were the keepers of the council fire in the center of the “longhouse,” in the modern day greater Syracuse area. The Cayugas occupied the finger-lakes area and the Seneca were the guardians of the western door in the modern Rochester-Buffalo NY area.” (NPS).

Peace ensued, and the Confederacy later proved pivotal to European relations and settlement.

I don’t yearn to live in the time of either Champlain or Hiawatha, but I admire something in both men: their ability to turn belief into knowledge.

The Onondaga warrior and the European explorer did not believe their paths were correct; they knew they were correct, destined to achieve their objectives. Belief and faith often leave wiggle room for hope, uncertainty, interpretation, and powerlessness, while knowledge is certain.

Both individuals knew their purpose with the same certainty that you know you’re reading these very words on this screen. We now live in the opposite condition: unprecedented information with a shrinking conviction.

Developments in science yield breakthroughs. With computers, the internet, and AI, we have the potential to calculate our way through almost any decision. In other words, it seems like we should be certain about everything we do, from day-to-day drudgery to matters of international conflict. Yet, today, 40% of teenagers are depressed, and more than half of adults are lonely. Scott Galloway’s powerful commentary should strike a nerve: “The most dangerous person in the world is a broke and alone young male.”

Science guides us through storms, yet in contemporary discourse, it appears vulnerable to conspiracy theories and spurious arguments; we’ve made science contestable. That’s one problem, but it may hint at a deeper issue. As a species, are we subconsciously recognizing that science does not, and never will, have answers to certain mysteries of humanity? Love, passion, and purpose are provable only to ourselves, within our own minds.

The open-endedness of these topics carves out a valuable space for myth, and, subsequently, belief and, ultimately, knowledge. This knowledge may not be scientifically informed, but it is necessary for human thriving and perhaps missing among the fragile, aimless, distracted, and depressed among us.

At times, religion and science trap us from either end; religion gets written off as silly and outdated, while scientific facts indicate a degree of hopelessness for much of humanity, including American youth. For this group, the numbers don’t add up favorably: buying a house, finding a job, meeting a spouse seems impossible, and the boogeyman of climate change is going to kill us. Riddled with relativistic arguments about right and wrong and self-loathing, America’s young people need a course correction.

How can we re-create the knowledge-based certainty of a Hiawatha and Champlain in today’s world? How could we infuse their certainty into the nervous minds of people raised on infinite options and thin meaning?

Perhaps religion would work; there’s an obvious appeal to such certainty, but there’s also a downside. Knowledge derived from a divine power can be harmful, if history is our guide.

Cultivating knowledge based on belief about mysteries we’ll never have a scientific explanation for involves trying. Trying involves struggle and failure, two things that petrify us. Trying (i.e., experience) helps us determine what’s worth believing in, moving us one step closer to a knowledge that steers us. Information and data can be parsed and validated, but they can’t tell you what to live for— that’s where experience comes in. Warriors and explorers of the old world lived a certain existence that wasn’t necessarily moral by today’s standards, but it unfolded within a structure built out of purpose.

"Love, passion, and purpose are provable only to ourselves, within our own minds." Sometimes I feel we have taken away the permission to feel and gain our own individual knowledge and experience with an expectation to instead connect with the flow of current, less resilient, humanity.

“ I felt convinced that I should be committing a grave offence if I did not take it upon myself to devise some means of bringing them to the knowledge of God.”

Ah, the old “bringing christianity to the savages” rationalization for genocide and territorial conquest. It’s a thing.