Looking Over my Shoulder

Battle in the Greens

Morning

When I step back inside to grab my gun, the mixed espresso and stale dog collar odor linger. Half a pill stuck in my throat. Creeping on the pine boards back to the kitchen sink, I leave a track of lug-sole-shaped mud.

Another day in the woods. See, bump, chase. Shoot? Maybe. I leave one outside light on, its dim, soft yellow beam casting enough brightness to let any other early riser know someone's around.

Two shooting stars this morning on my walk-in. Bored? Maybe. The familiar, the same, becomes tedious. This is boredom without mastery.

Midday

He's dead, and the chatter evaporates. Caffeine wore off hours ago. Not sure what drug could replicate this feeling. His hair is familiar, like a comforting object or an old friend. Blank, euphoric, and free, it's me going from one drug to the next, an addict. We talk like friends. “Thank you," I say. "Let’s go buddy," as I drag him over a log. "Just a little more to go," when I sit on his chest in a beech thicket.

Frost looks over my shoulder. Vermont’s pre-eminent summerer, his tracks may have climbed this high, but probably not. He was more gentleman farmer, the house cat with an ego. Swaddled by the social capital of those old yellow buildings. His tracks remained on a path familiar to those who make the Greens their summer playground. Ed Norton’s character in Fight Club asks, “If you could fight any celebrity, who would you fight?” I’d probably say Frost. I’m sure the state tourism planners huddled in Motpelier’s big building on the hill love him.

A rusted white shitbox of a Ram truck crawls away as I make it to the trailhead and have a clear line of sight to the parking area. “Good riddance, we don’t need any help,” I gripe. Grabbing his antlers, I loop the hooked end of an orange ratchet strap to his head and the opposite end to a loop that's part of the Tundra’s bed. Pull and lift, the strap makes a zipping sound, and his head is at least level with the truck. Tire tracks litter the snow, but no one is around for the heavy lifting. Hoisting his back half into the bed, I graze his hair again. Red hands and forearms, blood darkened and crackly like the paint of a Renaissance painting waiting for restoration.

What would the Iroquois have thought? It's their land, after all.

The overpowered truck roars with a push of a button: A V8 engine capable of towing 12,000 pounds that I use to cart around 190 pounds worth of grade-schoolers and 30 pounds of groceries. It’s equally as stupid as the rest of America's driving habits.

Our relationship is ending, the rift growing with each passing mile. Check-in station, gas station for chips, gummy bears, and Rolling Rock. At home, the tractor lifts, black diesel smoke puffing into his face when I turn the key. Betrayal. A junky stick of striped maple holds his legs apart in the 20-degree night sky.

I look out into the dooryard, flipping on the floodlight to see him slowly turning, his last dance with the stars. The dogs are in so they can't chew his snout off.

Playground State

Geographical place names, like sports, politics, or the weather, can be a source of endless debate. I recently learned that the ridge I'd been hunting for ten years is called a name I hadn’t heard before. I'd been calling it something else and didn't know, nor care, which name was accurate. Claiming knowledge of place names always struck me as a habit of the insecure, especially newcomers, like a way to prove they belong; Europeans did it, and new colonizers do it now. Or maybe I'm jealous since I can't remember shit like that.

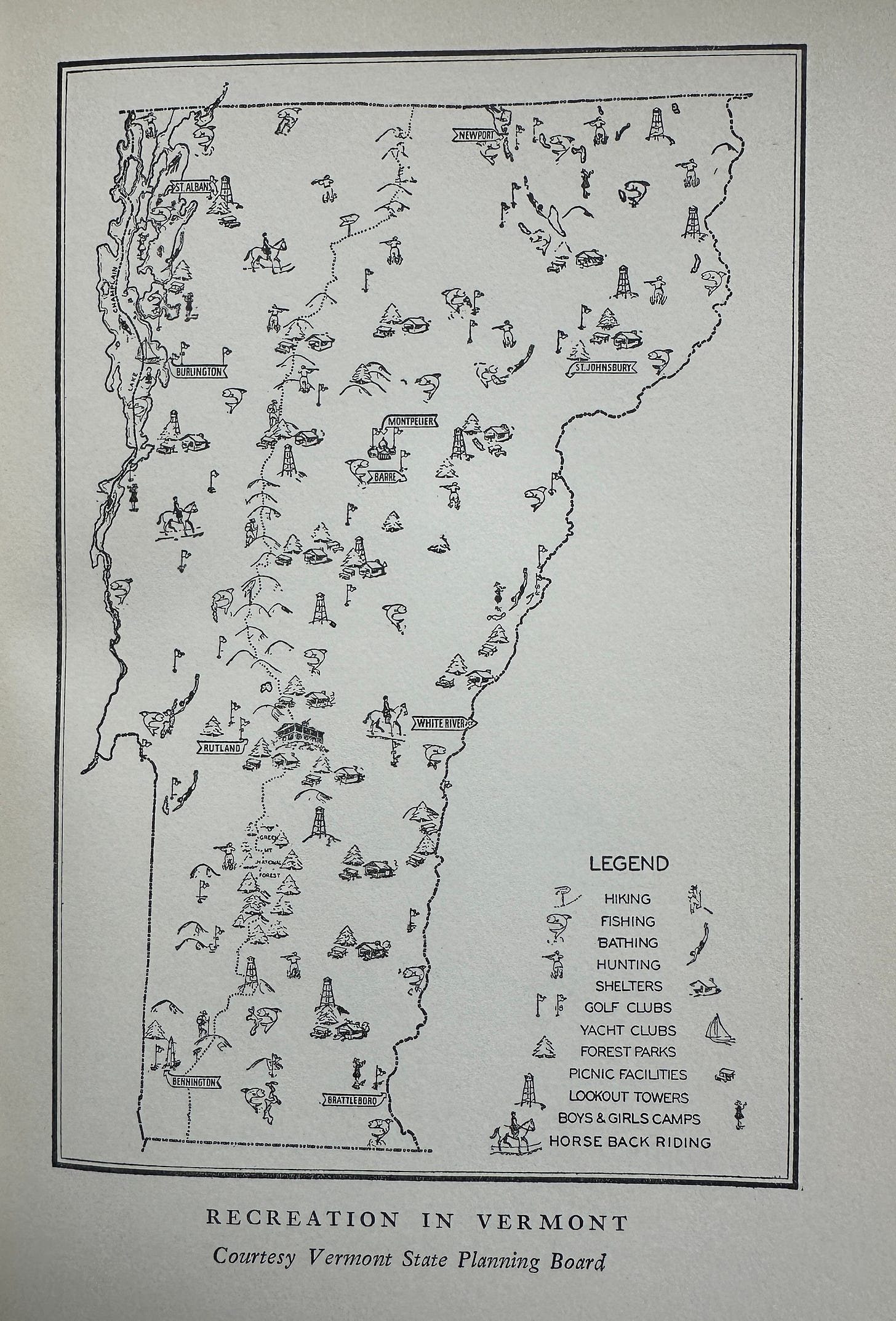

To the chagrin of many, including myself, the heart of Vermont is in the hospitality sector. “Vermont was born in a hotel,” declared Charles Edward Crane in 1937. Ethan Allen hatched his scheme to capture Fort Ticonderoga in the Catamount Inn. A map from the State Planning Board entitled “Recreation in Vermont” from Crane’s book assigns each part of the state one or more of the following categories: hiking, fishing, bathing, hunting, shelters, golf clubs, yacht clubs, forest parks, picnic facilities, lookout towers, boys & girls camps, horseback riding.

For at least 100 years, we've been trying to get people to visit and move here, so much so that it's part of the state's political and cultural identity. What also seems to be a tradition is that whether you've lived here for five months, five years, or five generations, you resent newcomers, often until you get to know them.

In the springtime, the muddy green mountains somehow produce arctic clear greyish-blue streams. Sysiphus would be at home maintaining water bars and drainage ditches. The jungle supplants the woods once the sun can no longer scorch the leaf cover of the light brown forest floor because of the tree canopy. Humid, buggy, and thriving. An abundance I love and hate. It's growing and providing but unfriendly to productivity. If you're just visiting, it's great, like when I visit a city, the traffic doesn't bother me too much, but if I lived there, I'd be consumed.

Evening

It's midnight now, and everyone is asleep except me and Maya, the half-Pyrenees bitch who’s staring at the glass door of the wood stove, dumbly looking at the tangerine flames produced by ash and beech logs. I walk back to the entryway, flip the light switch, and he's still there, hanging from the tractor bucket. Almost too cold for snow; a few flakes fall, looking like errant ash of a burn pile. There’s no greater sound than this silence, a dead stillness of cold, darkness, and belief the world is asleep. My second wind has kicked in.

7 AM. The kids are up, have eaten, and buckled. I have a separate Apple Calendar, “hunting,” listing critical dates: seasons, lottery deadlines, trips. Today marks the tail end of Vermont’s deer season. “Have a great day. See you after school!” This snow is lighter than air.

Fresh tracks cross the dirt road—the outside calls, as always. Like a poorly trained lab mix that finds a hunter's gut pile, I can't renounce. Another day, another delay, without typing, networking, dealing, hatching plans, or sitting on my ass. And what feels like an ongoing zombie-like homage to Musk, Bezos, and Zuckerberg.

The deer I chased that morning were likely descendants of the specimens introduced to VT in 1878 from New York state. This is a place of newcomers, human and animal alike.

Horizon

Rounding a knob, we have a clear view of the ridges, knowing full well it isn't that simple. From our vantage, the topography is comprehensible, and that's just a trick our feeble minds play on us. If we look at this same expanse as a relief, the spiderweb of undulations, drainages, and ridges is more truthful. So when I say to my buddy, “Let's head over to that ridge,” and he says, “Which ridge,” and I respond, "That one,” the conversation inches towards irritability, like trying to understand a tomb of a text that would’ve been better to convey over the phone. “See that dark green patch of conifers just below the outline of Jay Peak? Look to the right of that, and there’s a rock outcropping. See it? I think we should head towards that rock.”

With the next deer I kill, the betrayal comes sooner. It's a clean kill, a broadhead penetrating both lungs, exiting the far side of her pounding chest. Months of playing peek-a-boo with these cervids and the hints left by their hooves. Days filled with thinking and talking about them. A splinter that never gets pulled, left to fester and work itself out. Heal or infect? That’s the risk of the endeavor. Watching their coat turn from a rusty orange to a primal, darkish, chocolatey-milk brown, blending with the season’s mood.

Nice mood. Like we're right there on your shoulder, then in your head, then back again looking at it all from down the road.

Great job with this one!!