How I Stay Alive

Surviving in the wilderness when things go south

If you are more than an hour from medical care, loosen the tourniquet very slowly at the end of an hour, while maintaining direct pressure on the wound.

From “A Comprehensive Guide to Wilderness and Travel Medicine” by Eric Weiss, M.D.

This little book was published in 1997, and it came with the Adventure Medical Kit I purchased in 1999 when I started backpacking. Eastern Mountain Sports (EMS) was the go-to store for camping gear. For years, I kept Wilderness and Travel Medicine in the med kit but never used it for emergencies, instead relying on it for reading material. Books were too heavy to carry in my backpack, so I reached for Wilderness and Travel Medicine as my sleep aid when I lay awake in a lean-to on the Long Trail or somewhere on the Olympic Coast. Some parts of it got old, others didn’t, and I don’t remember anything other than the suggested technique for getting a foreign object out of your eye:

Take a clean Q-tip and wet it (hopefully with clean water).

Gently use the swab to scoop out the dirt, eyelash, leaf debris, or whatever is in your eye.

I still use this trick in both the backcountry and at home.

On February 17 of this year, New Hampshire Fish and Game conducted a rescue on the west side of Mt. Washington near the Ammonusuc Ravine. A solo hiker ascended the mountain, ignored advice from descending hikers to turn around, and then proceeded to become hypothermic. Predictably, this fella called for help. NH Fish & Game was able to utilize two trains from the Cog Railway to assist in the rescue. Key excerpts from the NH Fish and Game Report:

The Cog Railway was willing to start a special train, mount a snow blower on the front, and bring rescue crews up to the crossing of the Westside Trail.

Conditions on Mt. Washington as this first team started across were sustained winds at 90+ mph, a wind chill of -52°F, and an ambient temperature of -9°F.

[The hiker] had to be stripped of his wet frozen clothes and placed in extra gear that rescuers had brought. His boots were thawed out to a point that his frostbitten feet could go back in them with dry wool socks that rescuers provided.

After multiple recommendations that he go the hospital, [the hiker] refused treatment and “signed off” that he did not want to be treated.

[The hiker] called for a rescue after making these poor choices and putting himself in a situation that placed 11 other lives in danger in order to save his.

Accidents happen, and bad decisions are made; it’s easy when you’re committed to the journey you’ve laid out in front of you. Just get to the top and turn around quickly. After this part, we’ll be out of the wind.

More often than not, it works out and all we’re left with is a happy memory and relief when we’re back at the trailhead. The trip report above highlights poor decisions made by the hiker. He was ill-equipped for the conditions, was hiking alone in extreme conditions, ignored the advice of other hikers, and failed to re-assess the situation. His refusal to go to the hospital strikes me as unwise (and disrespectful to the eleven rescuers), though he claims to have allegedly driven himself to the hospital in later accounts of the incident.

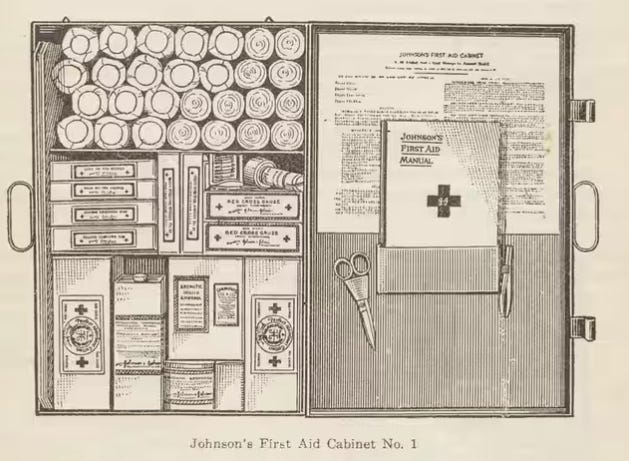

Johnson & Johnson’s original first aid kit conceived & designed for railroad companies. Year: 1888.

For years the only time I carried a med kit was when I was with my kids canoe camping. Day trips spent hunting, skiing, or hiking? I didn’t need it— too heavy to justify. Sure, I’d have some firestarter, a headlamp, and a whistle, but anything else seemed excessive. But as I read reports like the one above, I began making additions to my emergency first aid kit. An emergency bivy, backup battery…

Injuring myself was one thing, but putting rescuers’ lives on the line unnecessarily wasn’t something I was willing to do.

SOLO (Stonehearth Open Learning Opportunities) was established in 1976 by Dr. Frank Hubbell and Lee Frizzell. In a SOLO Wilderness First Aid Course from this past January, I learned useful techniques for a backcountry rescue (defined as 1 hour or 1 mile from definitive medical care). The objective of wilderness medicine is to:

Stabilize the patient.

Get the patient to definitive medicare care, thereby avoiding the need to utilize additional rescue resources/endangering more lives.

If the patient cannot be evacuated, then stabilize and monitor them until additional resources arrive.

I’ve re-invented my med kit based on this course to include the following:

Nitrile gloves

Jello

Aluminum cup (melting snow, dissolving Jello)

Elastic bandages

Roller Gauze

Gauze pads

Band-aids

Tube of Povidone-iodine

Tube of antibiotic ointment

Athletic tape

Moleskin

Safety pins

SOAP note, pencil, & Sharpie

Advil & Aspirin

This packs into a one-gallon bag:

Please let me know your thoughts on this med kit in the comments. Did I miss anything? Too much? Too little?

Appendix: Survival Kit

Interested in learning about my Survival Kit philosophy? See this post where I dive deeper into my Survival Kit contents.

Invariably, without deliberate consideration, we pack too much and some of the wrong stuff. Every backcountry hunter or angler should carry a well-planned first aid kit. Aside from obvious cuts and headaches, treatment for things like diarrhea, a burn, a fractured limb or a bullet wound should be considered.

In the minds of many trampers, survival kits are increasingly replaced by satellite communicators in practice, despite the possibility of not being rescued within 24 hours if weather is bad or satellite connectivity is limited. You need both. Your survival list is a good one.

Definitely take an EPIRB for emergencies and a Garmin Inreach Mini 2 or similar for messaging and weather reports.

I have an Iridium satphone to check in every second evening on my multi-day trips and as an extra emergency beacon (if I was able to reach for it, turn it on, find a satellite and activate the button).

With a chance of lacerations in hunting situations, QuikClot and super glue could be valuable. Duck tape is light and can be rolled around a small stick or even on itself. 10-15 feet is light could provide useful for compression, slings, and splints.