Gas Station Coffee

☕️ And the most fashionable brands 👕

Like most rivers in Vermont, the Missisquoi River is agricultural. Acting as an unintended catchall for farm runoff, big rivers like the Missisquoi weave through corn fields and towns, running over concrete dams, all the while collecting debris, both large and small. Nutrient runoff is a normal presence alongside less obvious occurrences such as asbestos fibers, found in tributaries of the upper Missisquoi, an unfortunate artifact of old mining activities.

This river travels 88 miles from start to finish, privileged to glimpse a view of nine towns, two counties, and two countries along the way.

Exiting into Missisquoi Bay, the water ends its journey, becoming part of Lake Champlain, which is really just a big river flowing south to north. Beginning in Whitehall and ending at the Richelieu River, the USGS continuously monitors the lake level.

Located at Latitude 44°59'46.6", Longitude 73°21'35.3", “on left bank at outlet of Lake Champlain in Rouses Point, and 1.0 mi south of Fort Montgomery ruins” is the Rouse’s Point, New York monitoring station. This is the point at which Lake Champlain enters the Richelieu River.

From here, the water, whose genesis was in the town of Lowell, Vermont, flows into the Richelieu and onto the North Atlantic by way of the Saint Lawrence River.

Samuel de Champlain traveled to the Champlain Valley in 1609 in search of enemies and driven by a desire to push further than Jacques Cartier, his predecessor from seventy years earlier. Not a born aristocrat, Champlain attained status early, and ego likely played an outsized role in his missions, evidenced by the number of namesakes left in his wake.

On my drive to the boat launch, I pass three Champlain Farms convenience store-gas stations. About 700' from the last Champlain Farms is the last damn of the Missisquoi River. And about three minutes from there, northbound on Route 78, is the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge.

Before our modern transportation infrastructure, going from point A to B expeditiously, involved water. Rivers, lakes, oceans, ice. Train tracks and roads proceeded river corridors because it was an easy way to go— flattish ground and familiar territory. Today, this translates to a noisy river. A paddle-able Vermont river not within earshot of a combustion motor is hard to come by.

Twenty minutes downriver from the boat launch, we trade engine break rumble for a jungle soundtrack starring hundreds of talkative birds. White perch, what we mostly fill our cooler with, is an invasive species, first observed in Lake Champlain in 1984. Opportunistic and aggressive, they thrive. The same could be said about Pierre-Esprit Radisson.

As Champlain followed Cartier, Radisson shadowed Champlain, albeit four decades later. Radisson's disjointed upbringing landed him in Trois Rivières, Quebec, at 16. As a peasant, Europe’s squalor didn’t promise much for Radisson in the way of upward mobility. Canada offered hope.

He looked for opportunity. While Europeans had whittled their natural resources down to a proverbial nub, North America’s wealth stretched beyond the northwestern horizon.

Captured by the Mohawk while hunting beyond the fort’s walls, Radisson’s life was spared. Curious by nature, learning the language and traditions of his adopted family, Radisson thrived. The Iroquois Confederacy was rich; they had leisure time, and community members didn’t have to beg or starve, unlike the underclasses of France. In the eyes of Europeans, Radisson would always be a peasant, but not in New France.

My canoe is a mile upriver from Lake Champlain on the Missisquoi. Much of Vermont, including the location of my canoe that day and the desk I'm writing on right now, was Mohawk hunting territory, the eastern gateway of the Iroquois Confederacy. Radisson paddled close by, possibly when he escaped from his adopted family. Yet, the chip-on-the-shoulder kept him firmly concentrated six degrees of longitude west and two degrees north of here on the Ottawa River.

Unable to convince the French of Hudson Bay's fur potential, Radisson and his brother-in-law tried again with the British, who bit. Their Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) today sells fashion products under the labels of Saks Fifth Avenue and Hudson’s Bay stores.

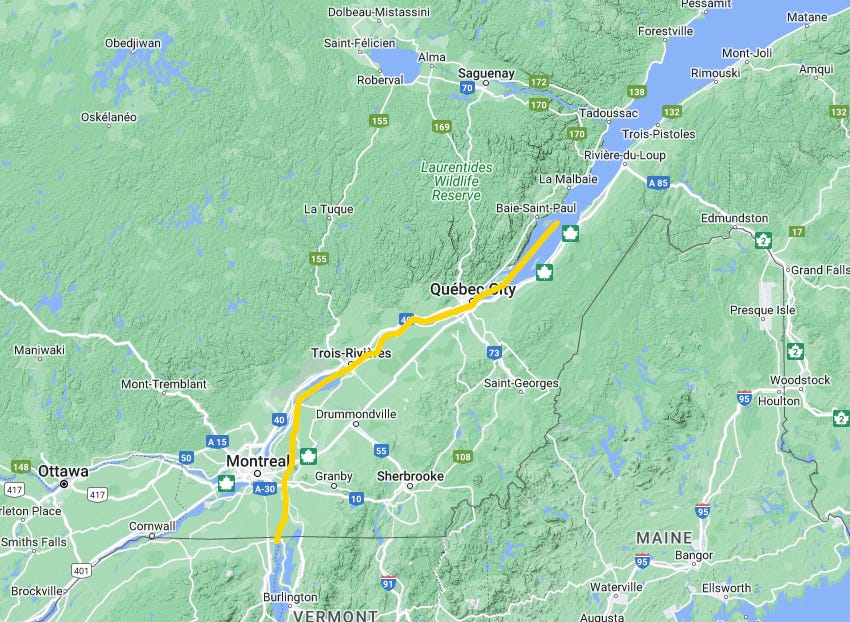

After tying the canoe to the roof rack, I stop in at the Champlain Farms. Gas pumping, I google map the closest HBC-owned store— in this case, La Baie d'Hudson is 90 minutes (55 miles) away in Montreal. Usually, I don't bring my passport on fishing outings, and this trip is no exception. But if I did have my papers: by the time I finish sipping my gas station coffee, I could be shopping at the department store Radisson founded nearly 250 years ago.

You might be amused to know that I recently bought (recyclable) Nespresso coffee pods at La Baie d'Hudson.