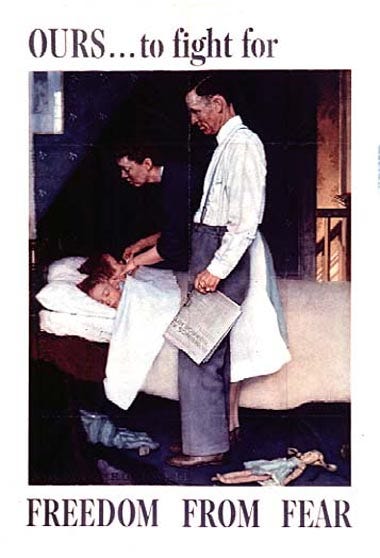

Fear Not

Cultivating an Adventure Mindset in Our Children

To adventure is to take a risk, and in today’s essay, I’m concerned with the idea of cognitive risk. Exploration requires persistence of inquiry, where skills, viewpoints, and approaches are sought out and manifested into physical reality.

I believe our and our children’s (un)willingness and (in)ability to take these risks is potentially one of the greatest threats to the United States.

“…let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself…”

Eighty years after Franklin Roosevelt’s death, and as Congress probes last year’s assassination attempt on Donald Trump, I witnessed a Class of 2025 senior say they were “scared” of the future during a June commencement speech. It’s a concerning trend: the CDC’s 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey found 40 percent of high-schoolers feel “persistent sadness or hopelessness.”

As the parent of two teenagers, I watched this fear build for years. Elementary school once taught my kids that the world is vast and worth exploring. Today, teachers and news broadcasts often frame most current events as some form of crisis. Teachers who spoke at June’s graduation ceremonies repeated the well-worn “follow your dreams” script, but the student speakers I heard described a world of conflict in tones of hesitation and anxiety.

Cultivation of Fear

Well before Covid, classrooms and Vermont media labeled most challenges as an existential “crisis.” Healthcare crisis, housing crisis, climate crisis—the list grows. Pre-Covid, a middle-school climate unit once warned my 12-year-old that the time to “save” the planet was gone; an alarmism that paralyzed more than it motivated. Alarm may rouse action, but when it becomes adults’ dominant note, children learn paralysis, not problem-solving. The CDC links poor mental health (which I contend chronic fear is a part of) to higher absenteeism and lower test scores, proof that the cost is real. Covid poured fuel on the panic: classrooms closed, screens replaced friends, and disinformation flooded every feed.

Fear alerts; courage decides.

Victory in Our Stories

If “fear is the mind-killer,” as Frank Herbert wrote in Dune, stories of victory supply the antidote. Had Frodo cowered in the Shire, mired in his own overwhelm, Middle-earth would have fallen. Tolkien shows us the remedy: name the danger, then act. Heroism is nonpartisan, yet progressives rarely answer spectacle with equal moral clarity. As Steven Pressfield reminds us, Spartan women were “the steel in the society’s spine”; bravery was never meant to be the property of any one gender or party. Young minds need that script more than another loop of catastrophe.

Fear should never be a student’s final lesson.

Courage Beats Spectacle

When protesters muddle their symbols, courage still cuts through: witness the injured candidate who, fist raised, shouted “Fight!” and electrified supporters. Courage, seen live, wins attention; our schools can teach the habit without theatrics. Opportunities for non-violent bravery abound. Speak to unfriendly press, hear out opponents, and condemn violence from your own side. Senator Bernie Sanders’ unscripted appearance on Joe Rogan in August showed the kind of open-minded bravery our culture needs more of.

Three Ways to Teach Courage

Make civics class a forum where students stand up and defend an idea—Florida, for example, pairs its required Civic Literacy Exam with $1.5 million in state grants for the Civics & Debate Initiative, seeding debate teams in every district.

Offer graduates a paid year of national service—the bipartisan Unity through Service Act of 2025 would create a federal service council and authorize stipends for “service-year” posts once Congress appropriates the funds, so teenagers learn by doing instead of doom-scrolling.

Anchor K-12 discipline codes to a simple free-speech pledge, modeled on the college-born “Chicago Statement,” now embraced by more than 100 universities, so every student learns that open disagreement is normal.

Critical Thinking Begins at Home

My teenagers and I dissect headlines, ask “Who benefits?” and test ideas against facts. They now spot the irony of driving six hours to protest carbon emissions, the chanting slogans that mask antisemitism, and the often performative nature of land acknowledgments. The habit is uncomfortable; teachers and peers sometimes discourage it, but the friction is the point. At our table, we tackle hot-button issues—immigration quotas, Middle East policy, tech & government layoffs—not to win arguments but to practice evidence-based thinking. We must model courage and curiosity so children meet challenges with “Let’s try,” “We’ll figure it out,” or “What’s the opposing view?”

Denying students (or anyone else) the chance to ask “why” in public turns classrooms (and society) into incubators for partisan reflexes. Ignorance breeds fear, and it has begun to feel normal.

The second half of FDR’s famous line about fear warns of “unreasoning, unjustified terror…which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” Teach and practice fearless inquiry, and all of us, including the Class of 2025, will turn retreat into advance.

Continue Getting Essays about Raising Brave Thinkers

Great points and references. Bravo!

This is fantastic.

To tell children of the existence of dragons without fostering the courage to face them is, at best, completely misguided.

They have lockdown drills at my son’s elementary school but don’t tell the kids “why”. Literally just a scary “hide in the corner” session for no reason. Okay, fear time is over- back to class!

Interestingly, the safety/ fear culture phenomenon in school DOES provide children an opportunity for some independent thought. By policy, my son’s class is not allowed to run on the mulch. Thus, he has a choice- mindlessly obey, or be more clever about when and how he runs on the mulch (a la Harry Potter and his rule-breaking friends). Almost like resistance training for your ability to think critically (provided one is using home time wisely- see “dinnertime debates”).

Thank you for the insight. I loved this piece.